The Valley, history and context

The Valle de Cuelgamuros – formerly Valle de los Caídos or Valley of the Fallen – is the major monument from Francoist Spain. Commissioned by Francisco Franco to celebrate his military victory and to house the bodies of the victors of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), it took some nineteen years to build. Penal labour was largely used for the construction process. The site was officially opened by the Spanish dictator on 1 April 1959, as part of the commemorations for the twentieth anniversary of his victory. It was, from the outset, only a memorial to the winners of the war.

As of 1959, more than 33,000 bodies of people who had died in the conflict started to reach its crypts. One of the first to arrive was José Antonio Primo de Rivera, founder of Spain’s main fascist party, Falange Española, who was executed in jail in Alicante in 1936, and had been transferred to the basilica in the Monastery of El Escorial at the end of 1939. In 1975, three days after his death, Francisco Franco himself was buried in the Valley.

For several decades – before and after his interment – the monument was a key symbol firstly for the dictator’s supporters and secondly, after his death and the democratization process, for those nostalgic for the Franco regime, who took part in celebrations every 20 November, the joint anniversary of the deaths of both José Antonio and Franco, the two historical figures who presided over the funeral hierarchy at the high altar of the Valley’s basilica.

Since 2000, with the birth of a new memorial culture in Spain – linked to transnational human rights paradigms – a part of Spanish society increasingly questioned the maintenance of the monument’s status quo. The discovery in the crypts of Republican soldiers and of Republican civilians executed by Franco’s forces and moved from mass graves without the permission or knowledge of their relatives, coupled with the continuation of commemorative events associated with the dictatorship and the absence of any systematic attempt to resignify the monument, have turned the Valley into the most controversial stronghold of Francoist memory.

This website seeks to show the monument in a new light, based on an analysis of its architectural, religious, patrimonial, funerary and political history. To be able to resignify the monument, endowing it with new meaning, we first need to be able to explain it. Any such explanation must go beyond the false account of reconciliation improvised by the dictatorship in the late nineteen fifties, decipher the motivations for its construction, and consider the labour and economic resources deployed in the postwar context.

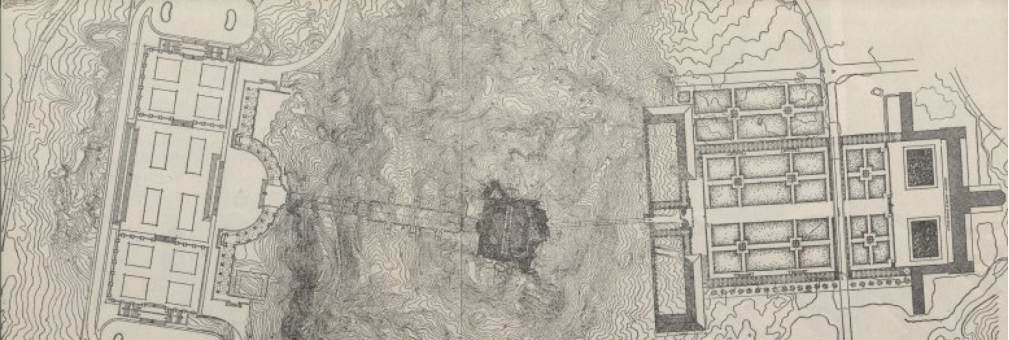

Other issues also require clarification, including the reasons for and meanings behind the architectural elements of which the complex is composed; the National Catholic worldview it embodies; the irregular process involving the transfer of thousands of bodies to its cemetery twenty years after the war had ended; its political mobilization as a refuge for Francoism even today; and its potential connections or contrasts with complex memory sites in other parts of the world.

To explain its historical context and its current anachronistic existence requires measures that range from the design of educational initiatives – essentially in digital formats and aimed at different targets – to provide the necessary tools to encourage open, inclusive and plural debate, so that citizens are fully aware of their own history, and able to detect and disable any potential drift towards totalitarianism or away from democracy. In this way, resignifying the Valley will allow critical and informed scrutiny of our recent history, with all its nuances, looking beyond propaganda and entrenched positions.

But explaining the Valley also means broadening the focus of our analysis beyond the local setting. The monument needs to be inserted into a wider framework of European memory, and into the globalized context and human rights cultures and practices of our contemporary world.

Planting the seed for a broader interpretation centre for the Valley, the information on this website will be expanded in the future to include: a timeline supported by contemporary and historical audiovisual materials; a research space with reference to archive documents, published academic texts and ongoing research projects; the transnational scenario in which the monument can be reinterpreted as part of a debate on the nature and management of memory sites in contemporary societies, and an institutional news section. It also offers visitors practical information about access to and use of the monument.